In my new year’s resolutions blog post, I made it a goal to co-author more with my friends, colleagues, and fellow bloggers. This post is the first attempt to realize the goal. My first co-author is Sejung (Sage) Yim, who is also a sociology PhD student at CUNY – the Graduate Center. We will reflect upon our identity formation as international students and immigrants in the United States through the experiences of how we have chosen to be called in various institutional settings.

According to social interactionists, by naming objects, we give meaning to them, and this serves as an integral part in forming our perceptions and our subsequent behaviors (Sandstrom 2018, p. 25). This process is not fixed, but it is undeniably affected by various circumstances depending on where one is situated. One might think that one’s first name is free from this meaning making process because, for most people, their names are not subject to change. However, this is not always the case. In this extended essay, we share our experiences regarding the use of our own real and constructed names as immigrants in the United States. We focus on how we have dealt with our own names in different ways, and how we have adapted or (re)claimed our identities in navigating our lives in new social settings.

Sejung/Sage’s story

I was born and raised in South Korea, where the overwhelming majority of the population is comprised of ethnic Koreans. Before moving to the United States, I never had to think much about my Korean name nor my Korean identity. My name was totally typical and “normal” in that it is comprised of three syllables—one for the family name and two for the given name. Since my name is so typically Korean, I never consciously had to make an effort to think about it in terms of my identity. I simply took both for granted.

When I first came to New York in 2012 to pursue my master’s degree at Queens College, I used my Korean name without thinking twice. I spelled my first name “Se Jung,” which is how it is written in my passport. However, I started removing the space between Se and Jung and decided to write my name as “Sejung” after a while. I did this because people and institutions (such as banks, government offices, schools, etc.) often mistook Se as my first name and Jung as my middle name. I would sometimes receive mail addressed to Se Yim or Se J Yim, which looked weird and awkward, since “Se” is only half of my first name. Although I couldn’t blame some default computer settings which treated the second syllable of my given name as a middle name due to the space between Se and Jung, it never felt quite right to see my name as being incomplete or truncated. But the spelling of my name wasn’t the only issue.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that my name is not easy for non-Koreans to pronounce—even though I do acknowledge that some Korean names are way more difficult than mine in English. When I introduced myself in class or in other social settings, less than half of the people would be able to remember my name, let alone pronounce it correctly. I tried to teach people the correct pronunciation by making it sound easier to English speakers, but very few were actually willing to put forth the effort. Although it is extremely difficult to communicate the precise Korean pronunciation of my name in English due to vast differences in accent and phonetics, it is not impossible to get a close-enough approximation. It just takes a little effort and willingness.

Here’s how to correctly pronounce my Korean name, Sejung Yim. The first syllable of my given name, “Sejung,” is pronounced like “Seh;” the “e” sound is short, as in “red” or “bed.” People tend to pronounce it more like “Say,” which is somewhat close, but conspicuously incorrect. The “j” in the second syllable of my name, “Jung,” is a typical American English “j” sound, as in “jealous,” and the “u” is a typical short “u” sound, as in “under,” and it rhymes with “hung.” The “y” in my family name “Yim” is silent, so in Korean, it is pronounced more like “Eem,” whereas when American people say it, it rhymes with “Jim,” and they pronounce the “y.” There is no short “i” sound in the Korean language, e.g., “slim” or “in.” I think that this clumsy and long-winded attempt to describe the correct pronunciation of my name is indicative of some of the challenges I faced.

Even some of my professors had trouble with my name, and they tended to avoid saying it. I guess either because they couldn’t remember it or because, understandably, they were afraid of mispronouncing it. When I would raise my hand in class to participate in discussions, some would ambiguously point at me rather than call me by name. This was notable because the majority of my classmates were called on by name. I was sure that the professors were not doing this with malicious intent, but it still hurt my feelings and sometimes made me feel insecure and isolated. I didn’t like that. At times, I subconsciously felt ashamed for not having an easy name for English speakers to pronounce or remember, even though there was nothing wrong with my Korean name. I gradually accepted my situation, though I sometimes felt sorry for myself for having to experience these unpleasant feelings.

Upon starting my PhD program at CUNY – the Graduate Center, I decided to adopt an English name. For the record, no one ever explicitly told me that I should choose one, nor did anyone ever ask me if I already had one. The decision was solely voluntary. Still, I must admit that there was some invisible pressure that made me think that I was making a good choice based on my past daily experiences. I had a feeling that if I changed my name in a way that would sound more familiar and less foreign or intimidating to others, I would become more recognized and approachable.

After much thought, I chose an English name, Sage. More precisely, it is kind of like an Anglicized version of my Korean name. I picked this name because it has a positive meaning (“wise,” or “someone who possesses wisdom”) and it also sounds fairly close to my real name. I didn’t want to just choose a random “American” name like Rachel or Emily. I wanted my new name to have some sort of meaning or significance because I felt that I needed to justify the change to myself. Deep down, I somehow didn’t like the fact that I had to create a new name. Although I took the initiative in coming up with a new name, I was annoyed because I felt like it wasn’t really based on my own free will. Rather, I felt like it was a compromise to make my life in the U.S. somehow smoother or easier. I wonder if others (not just Koreans) also felt the same way when for whatever reason they were creating a new name for themselves.

In her book, The Managed Hand: Race, Gender, and the Body in Beauty Service Work, Miliann Kang (2010) describes how some Korean manicurists voluntarily or involuntarily conform to their status as service workers by Americanizing their Korean names—for example, changing Eunju to Eunice or Haeran to Helen. Though I can’t draw a direct analogy, I think it also reflects how I felt when I Americanized Sejung into Sage. In a way, the reason I decided to go by Sage was not just for my own sake, but rather for other English speakers. Also, it was to help me adjust more smoothly in the U.S. as an immigrant. Yet, I didn’t fully realize that I was constructing a new identity at the same time I created my new name, Sage.

These days, most people don’t have a problem saying my name, and they tend to remember my name immediately. In addition, I don’t hesitate to tell my name to others (non-Koreans) anymore, regardless of whether they are classmates, professors, strangers, or retail/service industry employees. For instance, I no longer pause for a second to quickly think if I want to say my real name or an improvised, Americanized, or fake name while ordering a drink at a café or putting my name on a waiting list at a restaurant. I was surprised at how much easier my day-to-day life became simply because I chose an Anglicized name.

However, occasionally I find myself having an internal conflict for having two names. I introduce myself by different names depending on who I talk to. If I encounter other Korean or even other East Asian people, I introduce myself as Sejung or even by my full name, Yim Sejung (in most East Asian cultures, people conventionally put the family name first). On the other hand, if I meet non-Korean or non-Asian people, I introduce myself as Sage. It is almost as if I have two distinct identities.

I am Sejung and Sage at the same time. I am the same person, or at least that is how I am perceived by others. However, when I introduce myself as Sejung or I am called Sejung, my Korean side or personality naturally comes out more. My self-presentation and self-perception also largely depend on which language I am speaking at the moment. Since I feel most comfortable speaking Korean, Sejung feels more like myself, and I also realize that some of this is connected to associating Sejung with my Koreanness. To those who know me as both Sejung and Sage, and for those who more or less know how to correctly pronounce Sejung, I tell them that I prefer being called Sejung. This seems silly, and in a way, I feel as if I am making things unnecessarily complicated and confusing others. But I still do like being called Sejung even though I am now completely used to being called Sage.

When I introduce myself as Sage or when other people refer to me by that name, I no longer feel stress or anxiety that people will mispronounce or immediately forget my name. It often gives me more confidence adjusting to U.S. society. However, at the same time, I feel as if it gives me added pressure to fit into American culture. The Anglicized name affects how I think or behave, and it seems like I am subconsciously trying to conform to some kind of expectation others may have when they hear my name, regardless of whether people actually have any expectations of me. Moreover, every now and then, I face inner conflict for choosing to use an American name. Sometimes I feel like I am betraying my Koreanness by making a choice to compromise my real name so Westerners can pronounce or remember it more easily. Some may say I am making things too complicated. Perhaps I am. I feel like I have two identities, and I often feel trapped between the two as a result.

I write my name as Sejung Sage Yim, Sejung Yim, Sejung (Sage) Yim, or Sage Yim, depending on circumstances. My name is still listed as Se Jung Yim on most of my official documents, such as my passport, state ID card, and immigration papers. When I make initial contact with people, whether it is meeting them for the first time face-to-face or writing an email, I have to pick one identity that I want to go with. When signing an email after formally introducing myself as Sejung Sage Yim, I have to pause for a few seconds. Should I sign with Sejung or Sage? Which side of me do I want to emphasize? Or what is more appropriate? I now have some broad ground rules for dealing with my situational identity, but it is never a clear-cut thing. Honestly, sometimes I wish I never had an English name to begin with.

—Nga’s story—

“Do you have an American name?” is a question that I have received quite often in the U.S.

When I was in college, I often heard my fellow international students introduce themselves in the following manner: “My name is so-and-so, and I also go by Sophie or Jennifer or Katherine.” At first, this practice appeared bizarre to me, yet gradually I got used to the fact that in an American college context, one could choose how to be called. It was my first cultural “mini-shock” about the question of name and identity. One is free to choose how others perceive them vis-à-vis their chosen name instead of their name given at birth. This freedom to choose how to be called at times appeared liberating, but at other times, it confused me. In Vietnam, particularly in an educational context, people rarely choose another name other than the one given to them at birth. Choosing how to be called was a new practice to me. Even more complicated, I needed to remember how people preferred to be called, and be sensitive to their choice.

I did have an American name for a while. It was Lucy. The act of choosing an American name was not a response to the question whether I had an American name or not. I wasn’t forced to choose it because I felt embarrassed about my Vietnamese name: Nga. I chose it voluntarily out of necessity and good intention.

After my freshman year in college, I interned at Dekalb Workforce Development , where the local government provided the local workforce with training and workshops to prepare them for the workforce. I was working in a group that assisted local teenagers to get temporary summer jobs. Basically, the program collaborated with local businesses to create jobs for them. It paid teenagers on behalf of the businesses, hoping that the kids would gain practical job skills, and the business get to know them. Some did get hired by the business at the end of the summer. In other words, it was a social program that created jobs for underprivileged youth.

My job was relatively simple: inputting social work cases into a computer system. In order to manage almost 1000 cases, the program divided them into different teams. Each team was managed by a social worker, who would go to business locations to observe, talk to teenage workers, and business owners, or managers, document the youth’s behavior, and mediate conflicts should they arise. If one has ever worked as a social worker, one knows how dreadful the typing up notes after the visit/interview can be. It’s the worst part of the job because it takes a long time, and one does not know whether one should document everything. Deciding what is important, and what is relevant is the most difficult cognitive part. Then having to type all the hand-written notes into an administrative system is the second worst task. In addition, the system is often not working properly. It is slow, and like any extensive bureaucratic system, it’s confusing, and there is a lot of redundancy. My job as an intern essentially was to do the second worst task for social workers. That is to say, I had to collect cases, and type the hand-written notes into the system. In short, I helped them digitize their cases.

Most social workers enjoyed working with me because I was agreeable, efficient, and I seemed to type fast. They could not be any happier to outsource that task to me because after a full day driving around Atlanta, and talking to teenagers and business owners, they couldn’t care less about typing 2 pages of notes into an unreliable, bureaucratic computer system. I was happy to do the job because I didn’t have to go anywhere, yet I was able to learn so much about workforce development programs. That was all that I wanted for my first summer internship: learning how low-level bureaucracy worked in America. It gave me an overview of the job, how much paperwork was involved, and how much I didn’t want to work for the local government, nor work as a social worker.

In the first week at work, I realized that most people would call me “N” “ga” as if there were two syllables in my name. There is no “Ng” diphthong in English. It threw people off. The majority of social workers I worked with wanted me to help them, but there was an invisible distance between us, which was my name. They hesitated to talk with me or include me into office chats. I felt a burden on myself: a burden to make myself approachable, which would facilitate the team’s workflow. Having thought about getting an American name for a while, the internship experience was a decisive moment which nudged my decision to adopt an American name. I chose the name Lucy, simply because I was reading the the novel, The Time Traveler’s Wife, at that time. In one scene, the main characters went through a list of possible names for their their baby girl. “Lucy” stood out to me, as it was easy, and was interpreted as “you’re wonderful” in the novel. In Vietnamese culture, a name often has a meaning behind it. I thought it would work.

The summer went by, and the name stuck. I started introducing myself as “Lucy” instead of “Nga” in most occasions. It was confusing for close friends who knew me as Nga. It was also confusing for me, as I felt that I behaved differently as I took on the role of Lucy. It wasn’t about the shrinking invisible distance between me and others. It was about my conception of Lucy as a character. She was created to be an assistant, to be approachable, and relate-able; whereas, I had been always a rebel, a stubborn, and opinionated person. The two characters were not compatible in many ways.

The name stayed with me for quite a long time, until I moved to Germany. Then I worked as a research assistant with cultural anthropologists, whose language skills were superb, and whose cultural sensitivity made me aware that one did not have to use an Anglo-American name in an institution to facilitate bureaucratic efficiency, and lower cultural barriers. In addition, the majority of my friends outside of work were either Vietnamese, or Germans who spoke Vietnamese. Instead of asking whether I had “a German name,” they questioned why I was not using my Vietnamese name. Managing two identities as “Nga” and “Lucy” became increasingly burdensome as the amount of time that I spent with the Vietnamese community there increased. Toward the end of my time in Germany, I introduced myself solely as “Nga.” It was the moment that I reclaimed my Vietnamese identity, and I was very comfortable with it.

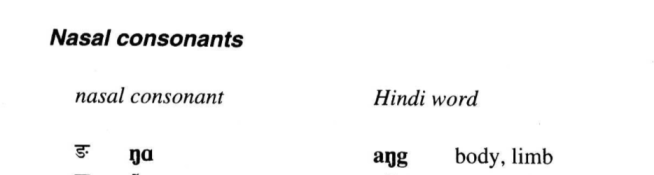

Graduate school started; I moved to New York. I decided that in order to keep my professional identity and personal identity consistent, I would only use one name – my real Vietnamese name: Nga Than. Regardless of how it gets mispronounced, I would stick with it. The majority pronounce my first name as “Nah.” It actually sounds endearing at times. Many a times, the word is butchered into two syllables: “N” and “Ga”. When that happens, I would try to make it easier by saying that it’s pronounced almost like /Nah/, as if the “g” is silent. Deep down I know it’s not, but the diphthong “ng” does not exist in English as a starting consonant. Plus I have never learned Vietnamese consciously, so I don’t know where my tongue position is either. The closest explanation of how to pronounce the “ng” that I came across in a Hindi textbook. The diphthong is considered as a nasal consonant, and it only exists at the end of Hindi words such as the following example:

If one is to conceptualize “ng” as a nasal consonant, one can imagine that it also exists in English as in the ending for “sing.” So let’s say “sing-A,” and you get it!

Sometimes I inadvertently make my interlocutor into a student of the Vietnamese language. They would learn a few spelling rules, a few phonetics, and a few tones. As long as they can process the information, I will gladly show them how to say a short sentence in Vietnamese. If they become overwhelmed with the amount of information, I will divert the conversation to another direction.

One might think that the amount of effort I have put in to make my name legible to an American is not worth it. Isn’t it easier to just keep the name Lucy so that the conversation could be smoother? Yes and No. It is yes from my interlocutor’s point of view because he or she does not have to consciously think about sounds that he/she is brought up to not be able to distinguish. My guitar teacher keeps telling me to practice listening to all different notes every day because “one is not trained to distinguish a lot of sounds.” It is a matter of practice, customs, and willingness to hear. From my side of the equation, there is a bit of friction when using the Lucy identity. It never felt right. I constructed an identity, but frankly I never fully imagined how this character would grow. She’s more fictional than real. She was like one identity mask that I had to put on when I interacted with people. Professional actors would not hesitate to say that playing a character is exhausting because they have to consciously think about how this person would behave. In reality, there is no script for me to play Lucy, but I always knew that she wasn’t me. Sometimes she existed independent of me. In other words, I suffered from an internal identity conflict, and after a period of time, I no longer desired to juggle multiple identities anymore. I quit!

Lucy came out of a fiction, and when I moved to New York, she was put back into the novel. I would live my life instead of hers. Nga is all I am now. And I am happy with this sole name.

Sejung Yim & Nga Than

February, 2018

New York